Classic Recording

Wed, 2022-07-06 16:58 — assr

Kate Bush’s Running Up That Hill from her 1985 album Hounds Of Love has been scampering up them charts in 2022 thanks to it featuring as the soundtrack to the crucial scene of the Netflix series Stranger Things. Let’s see, #1 on Spotify and iTunes, #1 in the UK, Top 10 in the US and counting… all after first ascending the (lower) echelons of International Chartdom 37 years ago. Is that some kind record, you ask? Indeed it is, in both senses.

Kate Bush was already a class act when David Gilmour discovered her at the age 16. Gilmour brokered her a record contract with EMI three years later, with a couple of Alan Parsons Projectiles in tow—arranger Andrew Powell and drummer Stewart Elliot. And Running Up That Hill is, with that impossibly catchy sixth interval in the melody of the song’s refrain, the impossibly catchy Fairlight sample, the brilliantly seamless transition from section to section, the lyrics, its uniquely weird and watery mix… a Classic Recording.

Can classic recordings be defined? Are they a thing? Can you learn classic recording? Absolutely. And classic recordings aren’t just ‘old’ recordings, on tape. Many old tape recordings should be consigned to a box in the garage for the 50+ brigade. Old does not equal good. Old is simply old. Good is good.

Classic Rock and The Foundations of Classic Recording

Classic recordings have no bigger standard bearers than classic rock records. With its beginnings in the late sixties sparked by the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Cream, Led Zeppelin, The Who, The Kinks, and The Doors, the seventies and eighties was classic rock’s defining period: Floyd, Queen, Supertramp, ELP, Yes, Genesis, Bad Company, The Alan Parsons Project, Foreigner, Fleetwood Mac and on and on. Artists sold records by the truckload and thank the lord they did because recording studios like the Record Plant, Abbey Road, Trident and The Village were notoriously difficult to get into and charged colossal fees. $1000 a day was perfectly reasonable. And this was a time that bands could spend months in the studio. Do the math.

Classic recordings are not, however, exclusively reserved for rock. Nor are classic recordings about sound, per se. Almost everything The Beatles recorded is a classic recording and they embraced everything from avante garde, like Strawberry Fields or A Day In The Life, to music hall, to folk and folksy, to pure pop.

So if classic recording is not about a genre, or a medium, what is it? As much as anything else classic recording is about an approach; an approach forged in large and expensive recording studios and, for the most part but only because it was the only game in town, recorded on analog tape and initially released on vinyl record.

Approaches cover a multitude of practices open to musicians who had the time and money (thanks to a friendly—I use this word in its loosest possible sense—manager or record label) to indulge their passion in terms of developing a unique voice, developing songwriting skills, experimentation with sounds, and general creativity from the first twang of a bass guitar on a tracking session to the final twiddle of a knob on a mix.

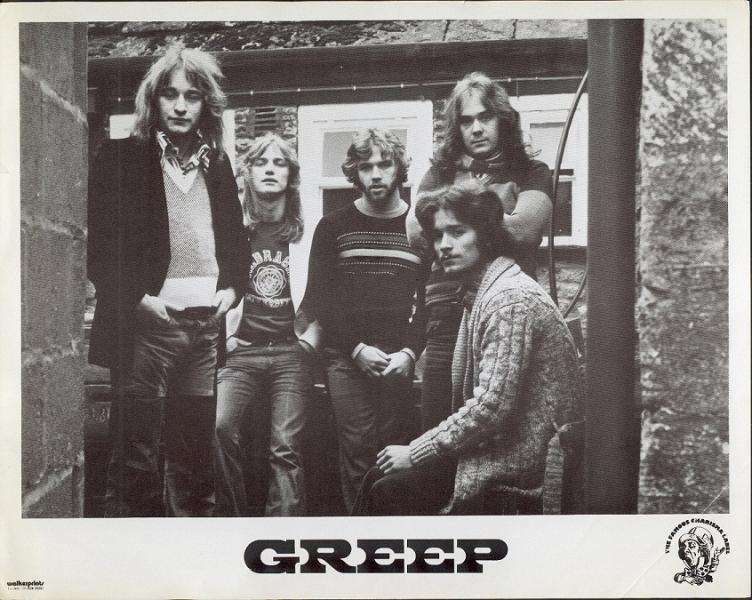

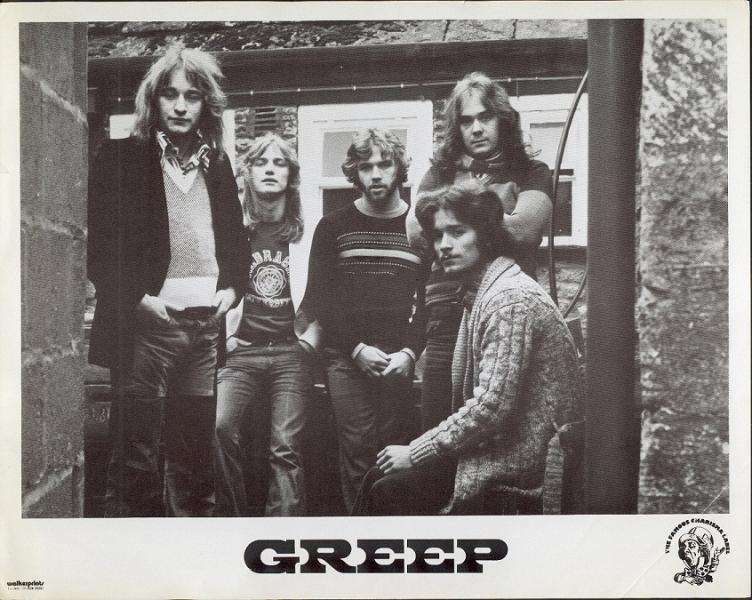

The first band I was in that got signed (to Charisma Records) was run by one Tony Stratton-Smith, a large ebullient and emotional chap who’d signed Genesis and was devoted to them, to horse racing, and to Bristol motor cars in equal measure. Oh, OK, maybe it was four-way: to heavy drinking: in The Ship, a pub on Wardour Street, the Marquee club, also on Wardour Street, and the Speakeasy club a few miles away, every night. Literally, every night.

‘Strat’, as he was universally known, was Indulger In Chief or Benevolent Benefactor if you wanted to be more charitable. If a young band needed three months on a farm in Devon to find its voice he’d pay for it. The motto of all this was that my band, while never becoming particularly successful, did at least begin to find its voice. Moreover it instilled in all its members a creative code that underpinned our every move, summed up by our favorite saying: “If you’ve heard it before, DON’T PLAY IT!” Clearly, Yes, Genesis and the entire prog rock movement sang their own tune to this hymn sheet, as also did so many straight rock or pop artists of the time. The point was ‘not’ to sound like everyone else. The point was to sound like you.

A Digital Divide

Modern digital recording technology has cut the cost making a record by almost 100%. Check. Democratization is generally a good thing. Digital generation and digital distribution have also democratized talent, which is still a good thing if you believe that cream generally floats to the surface. If the pool of music you’re currently floating on is now the size of the Pacific Ocean as opposed to Pacific Pond down at your local park, that’s OK too. Everyone should be able to have a go. But the whole approach to recording was the baby digital threw out with 9/10 th of the bathwater, along with its cousin, the whole recording process.

Many people look and listen with misty eyes and envious ears to tracks like Queen and Bowie’s Under Pressure, or Pink Floyd’s Comfortably Numb, or even such outliers as Don MacLean’s American Pie and feel that ‘they simply don’t make records like that anymore, as if there’s something in the digital medium or some algorithm in the wretched Daniel Eck’s Spotify that prevents great ‘classic recordings’ from being made.

Rubbish. There are plenty of great artists alive and well in 2022. Never mind the stellarly successful Billie Eilish and her bro Finneas, let’s also hear it for Sunny War, Shaina Shepherd, Britain’s Wet Leg and others whose status is anything but quo. What’s stopping more new classic recordings from being made is the almost wholesale triumph of marketing over content, and the tools and technology over time and the development of talent.

To better assess if, and if so how, classic recordings can be re-imagined we need to look at the constituent parts that make up a classic recording.

Let’s start with the song.

Going For A Song

Before there was any form of recording device a composer would ‘hear’ a melody or harmony in his or her head and then hastily scribble it down on manuscript paper or, if reasonably successful, bark at some lackey to do that for him/her. By the twentieth century, composers like Hoagy Carmichael were already just composing by ear and using recording technology and professional arrangers to establish and preserve their compositions for posterity. The likes of Carmichael and Irving Berlin (reportedly not only unable to read a lick of music but also unable to play an instrument except in a most basic fashion—he could only play the piano in the key of F#)—gave way to pop and rock songwriters for which the list who can’t write music on a stave is an order of magnitude greater than those who can.

But songwriting is not about notation or even transcription. Hoagy Carmichael once observed, as many have done since, that he didn’t so much ‘write’ his melodies as ‘find’ them. But the point is, he did find them and sometimes that process could take weeks.

On the face of it, digital recording media has done songwriting a giant favor because, again, seemingly, anyone can do it and can do it fast. To help us we have loops, samples, quantization, pitch correct, and now, should we want to get even lazier, we have the specter of AI. The thought of AI writing our songs for us is not so much terrifying but utterly pointless, except for the Daniel Ecks of this world who can then ‘legitimately’ not pay royalties to musicians and songwriters.

Songwriting is the manifestation of one or, increasingly, nowadays, for reasons I’ve yet to fathom thirty people’s creative musical or lyrical ideas. So, can a computer or an AI algorithm write a song? Duh! Of course they can. Point is, so what? It’s you, and your 29 friends, who will lose one of life’s most magical activities if you lose the ability to write a song.

The problem with digital technology, in terms of songwriting, is that it’s all too easy to skip over the actual songwriting bit and go straight onto, oh I don’t know, arrangement, production, mixing, mastering, marketing: straight onto YouTube or TikTok. If there’s one single reason why so much of today’s music seems so samey and sterile it’s because in place of a song there’s just an idea, or a loop, or a sample that gets repeated over and over, seemingly unchangingly, for 3m 30 secs.

Dare To Be Different

Try this: once a sound, or word, or phrase, or a beat gets those ‘I feel a song coming on’ juices flowing, DO NOT go straight into record on your DAW and start looping and adding more parts and playing with reverb plug-ins… in fact UNPLUG, and see if you can develop the idea further on your instrument. If your instrument is your voice, that’s OK too. Just sing, or rap, or experiment and record what you’re doing on your iPhone. Build a framework where you’re doing the work and not the computer and the music will come. It may take longer (though it could actually be quicker) but almost certainly it’ll be a better song.

In subsequent parts I’ll be be looking at the power and potential of live tracking sessions (musicians playing together), sounds, the concept of practice and how that relates to recording, mixing and much more.

Meantime, if you want to get a head's start on how to develop your classic recording skills, look no further than the Fundamentals of Recording & Music Production course, where Alan Parsons--he of countless classic recordings fame, starting with Dark Side Of The Moon--takes you step by step through all the twists and turns of this hopefully not dying art. www.artandscienceofsound.teachable.com (musicians playing together),

Classic Recording

By Julian Colbeck

Kate Bush’s Running Up That Hill from her 1985 album Hounds Of Love has been scampering up them charts in 2022 thanks to it featuring as the soundtrack to the crucial scene of the Netflix series Stranger Things. Let’s see, #1 on Spotify and iTunes, #1 in the UK, Top 10 in the US and counting… all after first ascending the (lower) echelons of International Chartdom 37 years ago. Is that some kind record, you ask? Indeed it is, in both senses.

Kate Bush was already a class act when David Gilmour discovered her at the age 16. Gilmour brokered her a record contract with EMI three years later, with a couple of Alan Parsons Projectiles in tow—arranger Andrew Powell and drummer Stewart Elliot. And Running Up That Hill is, with that impossibly catchy sixth interval in the melody of the song’s refrain, the impossibly catchy Fairlight sample, the brilliantly seamless transition from section to section, the lyrics, its uniquely weird and watery mix… a Classic Recording.

Can classic recordings be defined? Are they a thing? Can you learn classic recording? Absolutely. And classic recordings aren’t just ‘old’ recordings, on tape. Many old tape recordings should be consigned to a box in the garage for the 50+ brigade. Old does not equal good. Old is simply old. Good is good.

Classic Rock and The Foundations of Classic Recording

Classic recordings have no bigger standard bearers than classic rock records. With its beginnings in the late sixties sparked by the likes of Jimi Hendrix, Cream, Led Zeppelin, The Who, The Kinks, and The Doors, the seventies and eighties was classic rock’s defining period: Floyd, Queen, Supertramp, ELP, Yes, Genesis, Bad Company, The Alan Parsons Project, Foreigner, Fleetwood Mac and on and on. Artists sold records by the truckload and thank the lord they did because recording studios like the Record Plant, Abbey Road, Trident and The Village were notoriously difficult to get into and charged colossal fees. $1000 a day was perfectly reasonable. And this was a time that bands could spend months in the studio. Do the math.

Classic recordings are not, however, exclusively reserved for rock. Nor are classic recordings about sound, per se. Almost everything The Beatles recorded is a classic recording and they embraced everything from avante garde, like Strawberry Fields or A Day In The Life, to music hall, to folk and folksy, to pure pop.

So if classic recording is not about a genre, or a medium, what is it? As much as anything else classic recording is about an approach; an approach forged in large and expensive recording studios and, for the most part but only because it was the only game in town, recorded on analog tape and initially released on vinyl record.

Approaches cover a multitude of practices open to musicians who had the time and money (thanks to a friendly—I use this word in its loosest possible sense—manager or record label) to indulge their passion in terms of developing a unique voice, developing songwriting skills, experimentation with sounds, and general creativity from the first twang of a bass guitar on a tracking session to the final twiddle of a knob on a mix.

The first band I was in that got signed (to Charisma Records) was run by one Tony Stratton-Smith, a large ebullient and emotional chap who’d signed Genesis and was devoted to them, to horse racing, and to Bristol motor cars in equal measure. Oh, OK, maybe it was four-way: to heavy drinking: in The Ship, a pub on Wardour Street, the Marquee club, also on Wardour Street, and the Speakeasy club a few miles away, every night. Literally, every night.

‘Strat’, as he was universally known, was Indulger In Chief or Benevolent Benefactor if you wanted to be more charitable. If a young band needed three months on a farm in Devon to find its voice he’d pay for it. The motto of all this was that my band, while never becoming particularly successful, did at least begin to find its voice. Moreover it instilled in all its members a creative code that underpinned our every move, summed up by our favorite saying: “If you’ve heard it before, DON’T PLAY IT!” Clearly, Yes, Genesis and the entire prog rock movement sang their own tune to this hymn sheet, as also did so many straight rock or pop artists of the time. The point was ‘not’ to sound like everyone else. The point was to sound like you.

A Digital Divide

Modern digital recording technology has cut the cost making a record by almost 100%. Check. Democratization is generally a good thing. Digital generation and digital distribution have also democratized talent, which is still a good thing if you believe that cream generally floats to the surface. If the pool of music you’re currently floating on is now the size of the Pacific Ocean as opposed to Pacific Pond down at your local park, that’s OK too. Everyone should be able to have a go. But the whole approach to recording was the baby digital threw out with 9/10 th of the bathwater, along with its cousin, the whole recording process.

Many people look and listen with misty eyes and envious ears to tracks like Queen and Bowie’s Under Pressure, or Pink Floyd’s Comfortably Numb, or even such outliers as Don MacLean’s American Pie and feel that ‘they simply don’t make records like that anymore, as if there’s something in the digital medium or some algorithm in the wretched Daniel Eck’s Spotify that prevents great ‘classic recordings’ from being made.

Rubbish. There are plenty of great artists alive and well in 2022. Never mind the stellarly successful Billie Eilish and her bro Finneas, let’s also hear it for Sunny War, Shaina Shepherd, Britain’s Wet Leg and others whose status is anything but quo. What’s stopping more new classic recordings from being made is the almost wholesale triumph of marketing over content, and the tools and technology over time and the development of talent.

To better assess if, and if so how, classic recordings can be re-imagined we need to look at the constituent parts that make up a classic recording.

Let’s start with the song.

Going For A Song

Before there was any form of recording device a composer would ‘hear’ a melody or harmony in his or her head and then hastily scribble it down on manuscript paper or, if reasonably successful, bark at some lackey to do that for him/her. By the twentieth century, composers like Hoagy Carmichael were already just composing by ear and using recording technology and professional arrangers to establish and preserve their compositions for posterity. The likes of Carmichael and Irving Berlin (reportedly not only unable to read a lick of music but also unable to play an instrument except in a most basic fashion—he could only play the piano in the key of F#)—gave way to pop and rock songwriters for which the list who can’t write music on a stave is an order of magnitude greater than those who can.

But songwriting is not about notation or even transcription. Hoagy Carmichael once observed, as many have done since, that he didn’t so much ‘write’ his melodies as ‘find’ them. But the point is, he did find them and sometimes that process could take weeks.

On the face of it, digital recording media has done songwriting a giant favor because, again, seemingly, anyone can do it and can do it fast. To help us we have loops, samples, quantization, pitch correct, and now, should we want to get even lazier, we have the specter of AI. The thought of AI writing our songs for us is not so much terrifying but utterly pointless, except for the Daniel Ecks of this world who can then ‘legitimately’ not pay royalties to musicians and songwriters.

Songwriting is the manifestation of one or, increasingly, nowadays, for reasons I’ve yet to fathom thirty people’s creative musical or lyrical ideas. So, can a computer or an AI algorithm write a song? Duh! Of course they can. Point is, so what? It’s you, and your 29 friends, who will lose one of life’s most magical activities if you lose the ability to write a song.

The problem with digital technology, in terms of songwriting, is that it’s all too easy to skip over the actual songwriting bit and go straight onto, oh I don’t know, arrangement, production, mixing, mastering, marketing: straight onto YouTube or TikTok. If there’s one single reason why so much of today’s music seems so samey and sterile it’s because in place of a song there’s just an idea, or a loop, or a sample that gets repeated over and over, seemingly unchangingly, for 3m 30 secs.

Dare To Be Different

Try this: once a sound, or word, or phrase, or a beat gets those ‘I feel a song coming on’ juices flowing, DO NOT go straight into record on your DAW and start looping and adding more parts and playing with reverb plug-ins… in fact UNPLUG, and see if you can develop the idea further on your instrument. If your instrument is your voice, that’s OK too. Just sing, or rap, or experiment and record what you’re doing on your iPhone. Build a framework where you’re doing the work and not the computer and the music will come. It may take longer (though it could actually be quicker) but almost certainly it’ll be a better song.

In subsequent parts I’ll be be looking at the power and potential of live tracking sessions (musicians playing together), sounds, the concept of practice and how that relates to recording, mixing and much more.

Meantime, if you want to get a head's start on how to develop your classic recording skills, look no further than the Fundamentals of Recording & Music Production course, where Alan Parsons--he of countless classic recordings fame, starting with Dark Side Of The Moon--takes you step by step through all the twists and turns of this hopefully not dying art. www.artandscienceofsound.teachable.com (musicians playing together),