Julian Colbeck’s multi-part blog on what made classic rock (and classic country, classic folk, and classic hip hop) so compelling

In Part 1 I looked at the most important part of any popular music recording: the song, whether it's a carefully constructed, multi-part composition or just a loop knocked up on an MPC.

But having got the song, then what? Music biz execs used to say they could spot a hit if you just whistled it to them. Ha! More likely they couldn’t spot a hit if you wrapped it up in gold leaf and served it to them on a bed of Peruvian Flake. The Beatles were turned down by every label in the UK except Parlophone. Foreigner couldn’t land a deal with demos that included Feels Like The First Time. Missy Elliot was dismissed by one of the many execs who initially rejected her, simply as ‘too fat’ while Ed Sheeran’s multiple song rejections were bolstered by the observation that he was also (kiss-of-death on both counts) “chubby and ginger.” And so on and so forth.

It’s not enough to simply write a good song, you need to sell it, and by that I mean serve it up on a metaphoric bed of Peruvian Flake, wrapped in gold leaf. It’s called the ‘arrangement’ and this is almost invariably best manifested, if not created, by musicians playing and interacting with each other; refereed and then honed by a producer.

Who’s On First? Bass?

Before lifelong loopers and sample scouts get all foamy at the mouth, of course you can create—though often it might be more accurate to say curate—a decent track by yourself on Ableton Live. Music has always been a potentially solo sport ever since minstrels wandered the land. But the trap that 999/1000 DIY-ers hurl themselves into is to create/curate a bunch of self-indulgent, self-deluding twaddle where a single chord or note masquerades as a song, a breakdown with an offbeat kick drum constitutes an arrangement and the gradual opening of a filter passes for a performance.

Recording all the parts yourself, à la one-man-band, doesn’t have to be bad thing. Look no further than Billie Eillish and Finneas O’Connell’s When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? But don't overlook the fact that the O’Connell sibs had been studying and working on songwriting and production in their bedroom studio for donkey’s years. Nor the fact that they're an extremely talented—and dedicated—team.

Ditto Paul McCartney, who recorded ‘solo’ on McCartney (1970), Todd Rundgren on Something/Anything (1972), Mike Oldfield on Tubular Bells (1973), Prince on For You and Prince (1978 / 1979) and Steve Winwood on Arc Of A Diver (1980). But for every solo recorded classic there are probably 10,000 classic recordings made collaboratively.

Why?

The Eillishs, McCartneys, Rundgrens, Oldfields, and Winwoods of this world surely have vision and talent oozing out of them. And although Billie Eillish, Prince, and McCartney (twice, on McCartney II and McCartney III,) have repeated the concept, most one-man-banders tend to limit this to one time only. Why? Because it’s incredibly hard work. You need a surplus not only of raw talent but self-belief. And also because it’s a lot more fun to play music with other people.

Nowadays you can’t necessarily tell if a recording has been created by one person alone except to say that if it sounds like everything else that’s a bit of clue. One person can use the same loops, sounds and technology as the pack but it’s pretty unlikely that four people will be able to re-create the sound of another group of interacting players. Credits might run into double figures for songwriting and production these days but the player count often has a job getting beyond two or three.

The point is that, at the outset, most recordings now deemed classic have involved multiple musicians; playing with each other, at the same time.

On The Right Track

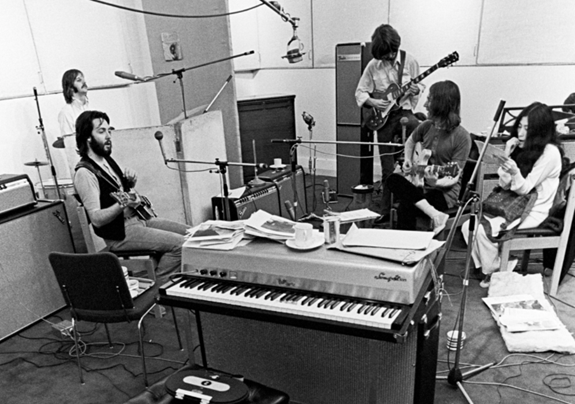

The foundation of this type of recording is the so-named ‘tracking session,’ where at least the nucleus of the band (rhythm section plus guitar or keyboard) play and are recorded at the same time. In 2022 we saw this gloriously brought back life in Peter Jackson’s Get Back movie where The Fabs not only recorded their instruments but the whole darned kit and caboodle.

For more mortal artists, a live tracking session mainly seeks to provides the song with its basic feel through interplay. Interplay involves listening to what your fellow players are playing at any given time and either stepping out of the way (a fill played over a fill rarely works) or consciously supporting a fellow player’s catchy slide, beat or run. In turn it’s then the job of the producer to listen to and spot these interactions on each run-through of the song and yea or nay them accordingly.

These types of interaction, that are not necessarily written into an arrangement, can constitute what’s commonly referred to as the ‘magic of the studio,’ in other words things that happen organically as opposed to bring pre-planned. Magic it may be but it’s not fairy dust sprinkled over the players as they entered the live room. It can be as innocuous as the bass player forgetting where they were in the song and playing E instead of C or the drummer accidentally continuing the fill for an extra beat.

Feel—magically enhanced or not—is something that happens when musicians play together, listen to each other, and then react as a unit. With all the pitch and timing correction in the world it’s extremely hard to ‘dial in’ feel by numbers. Maybe not quite in the league of monkeys’ problem with creating the complete works of Shakespeare simply by staring at a typewriter, but the magic of the studio is much less likely to strike if it’s just you staring at a computer screen.

Dark Side Of The Moon engineer Alan Parsons is adamant that this iconic record would not have turned out as it did if Messes Waters, Gilmore, Wright and Mason had not been playing together, live, in #3 Abbey Road on the initial tracking sessions. Much as this landmark record still sounds immaculate—and with great seeming separation between the various instruments—what you’re hearing is skillful writing, arranging, playing and recording.

Most of us do not have Abbey Road # 3 to play in, Waters, Gilmore, Wright or Mason to play with or Alan Parsons to play to. ‘Spill’ (where the sound of one instrument is non-intentionally picked up on the recording of another) may not be a deal-breaker but it’s still rarely desirable. A tracking session should ideally try to preserve as much separation as reasonably possible so that if you do need to replace a part, or a section, you won’t suddenly have a problem where a new part is dramatically different in sound to the one you’re replacing or that the ghost of the original won’t be heard as spill on other instrument mics.

Spill can be minimized by baffles, by the positioning of the microphones, or lack thereof: Try recording as many instruments as you can ‘direct’ i.e. not using a mic at all. Also by volume, or lack thereof. Easier said than done if you have an acoustic drum kit and drummer whirring away beside you but something to bear in mind. Ditto issues of a tracking session where acoustic drums and acoustic piano are being recorded simultaneously. Strangely, and within reason, you can often get more usable results by placing these instruments relatively close, and covering the piano/mics with heavy blankets. If two sound sources are, say, at opposite ends of the studio, you may well run into problems of timing, i.e. the spill being delayed and therefore much more noticeable.

There’s always a solution. The big thing is simply to give a live tracking session a try. Even if you’ve got a song pretty well dialed on Logic or ProTools or Ableton Live with yourself being all things to all players, try assembling a small coterie of players in a room and record the song—at least its most elemental parts, drums, bass, a guitar, and a keyboard pad—live. If you must ‘correct’ or fly in some repairs that’s OK but make sure what you fly in doesn’t make the feel fly out. Perfection is seldom fun to listen to. People are not perfect. Musicians certainly aren’t. Music shouldn’t be.

Character Assassination

The final and obviously vital piece of the live tracking session puzzle—and really one should say beauty—is the player.

Today, when not only sounds but loops are but a click away on Splice, the character or skills of any particular bass player, drummer or guitarist have seemingly become moot.

Looking back at some early classic rock classic recordings it’s ludicrous to imagine drummer Mick Fleetwood playing with any other bass player than John McVie on Rumours. Or Nicko McBrain and Steve Harris with Iron Maiden, Sly and Robbie, Chad Smith and Flea…

It’s easier for members of a band to be simpatico since being simpatico has presumably led them into being in a band together in the first place.

Instant simpatico is one of the great but rarely recognized skills of the professional session player.

Great session players manage, simultaneously, to have a chameleon-like ability to fit in with what and whomever else they are playing with AND still bring their own energy and character to the session. Think of bassists like Tony Levin or Carol Kaye, guitarists like Tim Pierce or Greg Leisz, keyboardists like Rami Jaffee or Greg Phillinganes, or the king of keyboard sessions, Paul Griffin.

Skills vary. Styles vary. But most recordings, almost regardless of style except, say jazz or progressive rock, tend to benefit from simple parts even if simple sounding is not necessarily simple to play.

Sound Judgment

Aside from the sameness of the notes or beats, the other dismal aspect of using pre-digested loops over live players is sameness of sound.

Classic records frequently have at least one distinctive sounding part – a guitar riff, a bass, a keyboard hook. In this respect modern recording tools offer no excuses whatsoever as even most pre-teen’s rig is riddled with VSTs bursting not only with presets but tools to twist and turn any sound into anything else.

But sound is not only the texture and tone of synth line or an effect on a guitar, it’s also natural characteristics: drums that ring sympathetically with neighboring drums, the squeak and thud of a piano pedal, string squeak on an acoustic guitar. Sometimes these can be annoying but sometimes they can enhance the rhythm or overall sound and be a vital component in the recording. The trick is not to automatically surgically remove artifacts before checking that you’re not surgically removing character as well.

Classic recordings are riddled with attempts to overcome or disguise a technological limitation when the recording was made. Or not. Surely Phil Spector could have captured a better sounding grand piano than what was used on John Lennon’s Imagine, which frankly sounds like it was recorded on cellotape. But it works. It’s distinctive, it’s non-pretentious. It was the right call.

Finally there’s the sound and sound limitations of the recording medium. Between 1950-1990 recording technology was exclusively analog tape based. From the 1960s the amount of linear ‘tracks’ that could be delineated on piece of tape went from 2 to 4 to 16, finally settling on 24 before digital re-wrote the whole chapter.

As an analog medium there is and was a certain amount of coloration – in part due to engineers exceeding recommended record levels, known as tape saturation, but in part just the limitations of the highs and lows that tape could either capture or reproduce, certainly on vinyl. At the time these limitations were universally felt to be a bad thing but, curiously, limitations also have the effect of making a record feel warmer, more cohesive, more human even.

The ugly step sibling of this was the limited number of tracks available to record individual parts on. Famously, if incredibly, The Beatles Sgt. Pepper was recorded on a 4-track tape machine. Dark Side Of The Moon on 16-track.

Although The Beatles could—and did—utilize several 4-track tape machines and bounce tracks together, this was still a cumbersome and restrictive process.

Or was it?

There’s a school of thought that says a degree of pain and suffering is a necessary part of the artistic process. Vital even. A limitation is rarely an insurmountable obstacle, it’s just a problem to solve or find a workaround and in that quest great art can often get produced.

So how does a producer working in 2023 on a digital audio workstation offering unlimited tracks (much less without the surprisingly useful period of tape ‘re-winding,’ which gives everyone’s ears and brains a break), unlimited sounds, unlimited undo and unlimited editing capability back themselves into a technological corner and force themselves into finding creative solutions? Hard to de-invent, but what you can do is stay on top of—and use—the technology and not become a slave to it. Jack White is a great proponent of self-imposed deadlines or self-restricting practices.

We’ll look at the subject of ‘perfection’ and whether we can actually handle the truth, in Part 3.