Evolving DAWs

Julian Colbeck reflects on the birth and growing pains of digital recording as Keyfax NewMedia turns twenty-five.

Part 2. Coming To America

The UK is a challenging place to live and work, especially if you’re in music.

When I was a touring musician there was nothing quite like returning to London from a gig in the midlands at 2AM on a rainy Saturday with nothing but the Watford Gap (a ‘service station’) and its fare of greasy whatever to look forward to before you crept back into a freezing flat ("apartment") with only the girlfriend’s toes for warmth.

The late night food situation in the UK may have improved modestly in the past thirty years but the country is still not built for travellers, as it is in the USA.

And from my experience in 1994, nor was it built for new businesses.

Credit Squeeze

The initial problem was not so much getting sales but getting the money. In spite of owning a house and having a spotless credit record Barclays, my bank of some twenty years, refused to give us a credit card facility—i.e. the ability to ‘receive’ (not borrow)—money by credit card payment. “Too risky” they said. And that was that.

It’s a half empty / half full glass thing and, decamping to the US some months later, a guy called Ron, who didn’t know me from John Adams, got in touch after having registered the business at the County Court and just said “You’re going to need a credit card facility!” Ron, who looked like he’d stepped out of a Quentin Tarrantino movie came through and I hope he still gets a piece of the action because over the next few years Keyfax put millions of dollars through that company. Nice one, Ron. Barclays? You suck.

Life’s A Beach

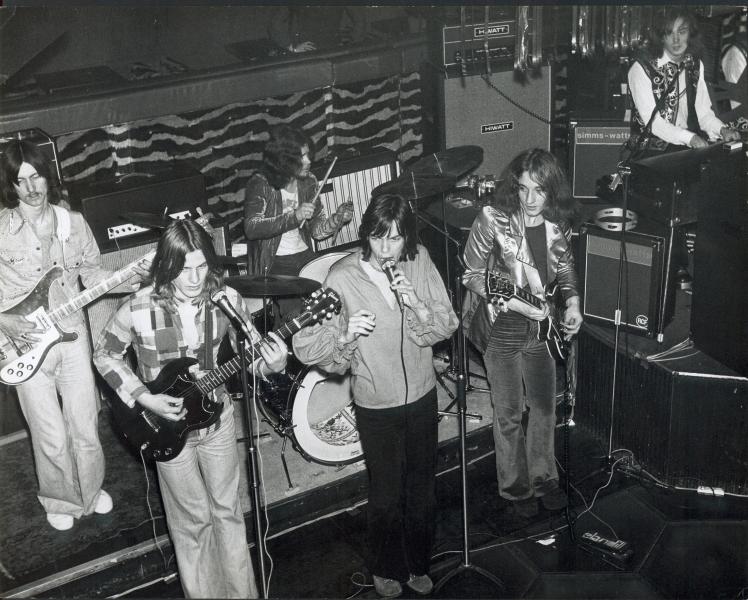

Landing in Santa Cruz, CA as a technically illegal alien, the US could not have been more welcoming. In addition to brown leather jacketed Ron, I was overwhelmed by support from local music companies: E-Mu’s Marco Alpert, Q Up Arts’ Doug Morton, Keyboard magazine, local musos like ex-Doobies Dale Ockerman, and Tiran Porter (who’d famously announced to me on tour with my band Charlie that their upcoming album “wasn’t my fault. It’s terrible…” talking about Minute By Minute.).

Recording MIDI-a

Recording MIDI-a

The concept behind Twiddly.Bits was having real players record loops on the MIDI equivalent of their instruments. Recording drums (using drum pads, mainly Roland V Drums) was relatively simple. As Alan Parsons would say to me years later, the secret to getting a good drum sound is get a good drummer. And that holds true with MIDI recording as well. After Bill Bruford we also recorded Hugo Degenhardt (my bandmate with Steve Hackett) and Gavin Harrison (King Crimson, Porcupine Tree, The Pineapple Thief) and the success of the Drums & Percussion library inspired us to record several new drum loop collections, notably MIDI Breakbeats. We also, and bravely, tackled a genre not typically beloved by programmers: country music. It fell to me to do the initial recording of Dwight Yoakham’s fiddle player Scott Joss, more recently known for his work with Merle Haggard.

The key to record convincing MIDI performances is not quantizing, and not cleaning up every little ghost note or what might appear to be extraneous data. We used a Zeta violin MIDI pickup and, in order to be able to capture articulations like double-stopping, decided to record multi-timbrally, i.e with each string on its own MIDI channel. During the recording Scott had the sort of fixed, pitying expression of a man looking at miniature poodle trying to mount a St. Bernard. Mining this data for nonetheless usable loops was also both an hilarious and hair-tearing exercise and I’m not sure even our genius programmer and editor Dave Spiers back in the UK ever quite recovered.

The key to record convincing MIDI performances is not quantizing, and not cleaning up every little ghost note or what might appear to be extraneous data. We used a Zeta violin MIDI pickup and, in order to be able to capture articulations like double-stopping, decided to record multi-timbrally, i.e with each string on its own MIDI channel. During the recording Scott had the sort of fixed, pitying expression of a man looking at miniature poodle trying to mount a St. Bernard. Mining this data for nonetheless usable loops was also both an hilarious and hair-tearing exercise and I’m not sure even our genius programmer and editor Dave Spiers back in the UK ever quite recovered.

Twiddly.Bits MIDI sample loops began to catch on, selling not only in the US but all over the world. One of Doug Morton’s recommendations was the Japanese distributor Media Integration, who purchased crates of product at a time. In 1998 I visited them in Tokyo, taking part in a live MIDI loop contest at a Roland Sound Party, trading loops in front of a sizeable if bemused audience with local rival company Idecs, flaunting their Hypergroove series. “And now, a bass loop from Keyfax….!” Bizarre but beautiful. And yes, since you ask, we like to feel we ate their sushi.

Twiddly.Bits MIDI sample loops began to catch on, selling not only in the US but all over the world. One of Doug Morton’s recommendations was the Japanese distributor Media Integration, who purchased crates of product at a time. In 1998 I visited them in Tokyo, taking part in a live MIDI loop contest at a Roland Sound Party, trading loops in front of a sizeable if bemused audience with local rival company Idecs, flaunting their Hypergroove series. “And now, a bass loop from Keyfax….!” Bizarre but beautiful. And yes, since you ask, we like to feel we ate their sushi.

Hard Sell on Software Sales

At this time, in addition to producing multiple new MIDI sample collections—Drums and Percussion, Electric & Acoustic Guitar, Country, and The Funk—it had also come to our attention that the world was going increasingly soft. Dave Smith’s Seer Systems. Reality, the world's first professional software synthesizer for the PC, came out in 1997 and sound cards, notably those made by Creative Labs, who had purchased our friend E-Mu back in 1993, dominated the burgeoning market with the SoundBlaster AWE32. We created custom libraries, both for the AWE 32 and for PC people's favorite DAW, Cakewalk.

But when it came to performing, was music under the control of a blob of plastic on wheels really the best answer? Increasingly, I felt, not. Music should be more of a kinetic, immediate cause-and-effect thing. Do something, hear something. So, with some initial skepticism from my partners and subsequently a ton of skepticism from the world at large, I came up with the idea of a MIDI Performance Controller: A box of knobs hard-wired to several key MIDI Continuous Controllers that you could play in real time. My son was an avid Game Boy user and I figured Phat.Boy was a pretty decent name for a device that allowed you to tweak and control sound. Well, MIDI; but sound was the end result.

The key to Phat.Boy was that it was instant. Plug it into a GM or GS synth or soundset and it worked. No drivers, nothing to set up, download, install, fiddle about with. At first the community was all ‘Oh no, we need to be able to assign different controllers, customize parameters.’ Arrogantly, perhaps, I figured that even if there were 1001 parameters you could control there was probably only a dozen you actually/typically would. And here they are! I felt that, at least initially, people would appreciate the freedom of having lmited controls and just be able to focus on the music. I remember going to a game convention in San Diego in 1999 and seeing the expression on people’s faces who, for the first time, felt like they were able to control music. And in real time. Magic stuff.

Phat.Boy did become something of an ‘overnight success’ and, in addition to breathing new life into the Roland Sound Canvas and Yamaha XG module business (I remember Yamaha seeing us at a NAMM show and literally not believing what was coming out of a Yamaha MU128) and soon Phat.Boy became the de facto ‘hardware controller for soft synths.’ Propellerhead and Steinberg distributed Phat.Boy with Cubase and Re-Birth under the name Birth Control! Who says Swedes and Germans don’t have a sense of humor?

Phat.Boy did become something of an ‘overnight success’ and, in addition to breathing new life into the Roland Sound Canvas and Yamaha XG module business (I remember Yamaha seeing us at a NAMM show and literally not believing what was coming out of a Yamaha MU128) and soon Phat.Boy became the de facto ‘hardware controller for soft synths.’ Propellerhead and Steinberg distributed Phat.Boy with Cubase and Re-Birth under the name Birth Control! Who says Swedes and Germans don’t have a sense of humor?

The Beginning of the End of the Beginning

It was an exciting but challenging time juggling hardware and software products and juggling two sets of people, one still in the UK and one freshly ensconced in a suite of offices downtown Santa Cruz: modest, but a major step up from the basement of my house in Aptos.

By 2001 Phat.Boy and Twiddly.Bits were selling in Guitar Center and in countries all over the world. But, as so often happens, internal pressures between the UK and USA were building and our world would soon both be torn apart and reborn shortly before 9/11.

In Part 3, the phenomenon that was the Yamaha Motif. Working in social media before there was such a thing as social media.

But no matter. Into this heady mix of musical mayhem fluttered a request from a magazine to review yet another collection of appalling MIDI File songs; replete with over pitch-bent sax parts, wooden drums (and not in a good way), and clanky guitar parts that sounded like they’d been played by someone wearing boxing gloves. Only the pianos and organs sounded remotely like their namesakes. Hmmm. Why is that, I wondered? Maybe it’s because all this rubbish had been played (into a ‘sequencer’) from a MIDI keyboard?

But no matter. Into this heady mix of musical mayhem fluttered a request from a magazine to review yet another collection of appalling MIDI File songs; replete with over pitch-bent sax parts, wooden drums (and not in a good way), and clanky guitar parts that sounded like they’d been played by someone wearing boxing gloves. Only the pianos and organs sounded remotely like their namesakes. Hmmm. Why is that, I wondered? Maybe it’s because all this rubbish had been played (into a ‘sequencer’) from a MIDI keyboard? I had been the proud owner of an Atari 1040 ST computer for some time. The Atari had no RAM and no hard drive (don’t be silly). For storage it had a disc drive that could store a whopping 720KB—yes, kilobytes--of ‘darta’ on 3 ½ inch floppy discs.

I had been the proud owner of an Atari 1040 ST computer for some time. The Atari had no RAM and no hard drive (don’t be silly). For storage it had a disc drive that could store a whopping 720KB—yes, kilobytes--of ‘darta’ on 3 ½ inch floppy discs.

Sign up for the Webex Webinar

Sign up for the Webex Webinar

James Husted is the designer and co-founder of Synthwerks, a widely acclaimed producer of Eurorack performance control modules. In addition to being a committed Eurorack player himself, James has spent many years in education, teaching electronic music. James is also an accomplished designer who has worked for numerous music and audio companies including LOUD Technologies, Digital Harmony, and Symetrix.

James Husted is the designer and co-founder of Synthwerks, a widely acclaimed producer of Eurorack performance control modules. In addition to being a committed Eurorack player himself, James has spent many years in education, teaching electronic music. James is also an accomplished designer who has worked for numerous music and audio companies including LOUD Technologies, Digital Harmony, and Symetrix.

Beth Hollenbeck is both a highly skilled educator, developing and implementing recording arts and songwriting classes that incorporate business skills and practices used for becoming a professional in the music industry, and a musician and performer in her own right with several successful records under her belt. Beth’s vision and tenacity earned her congressional recognition in 2011 as educator of the year, the same year she was awarded a GRAMMY for the creation of her music production program at Scott’s Valley High School. Beth has also been recognized in the NAMM Foundation’s Best Communities for Music Education in 2013, 2014, 2016 and 2017.

Beth Hollenbeck is both a highly skilled educator, developing and implementing recording arts and songwriting classes that incorporate business skills and practices used for becoming a professional in the music industry, and a musician and performer in her own right with several successful records under her belt. Beth’s vision and tenacity earned her congressional recognition in 2011 as educator of the year, the same year she was awarded a GRAMMY for the creation of her music production program at Scott’s Valley High School. Beth has also been recognized in the NAMM Foundation’s Best Communities for Music Education in 2013, 2014, 2016 and 2017.

Julian Colbeck is the co-creator, producer and writer of Alan Parsons' Art & Science Of Sound Recording (ASSR) projects. Julian spent 25 years as a professional keyboard player working with the likes of Charlie, John Miles, Steve Hackett and Yes/ABWH. Julian began writing about music technology in 1986 with the publication of Keyfax, A Buyers Guide published by Virgin Books. He has since written more than a dozen books on music and music tech while also assuming duties as the CEO of KEYFAX NewMedia Inc.

Julian Colbeck is the co-creator, producer and writer of Alan Parsons' Art & Science Of Sound Recording (ASSR) projects. Julian spent 25 years as a professional keyboard player working with the likes of Charlie, John Miles, Steve Hackett and Yes/ABWH. Julian began writing about music technology in 1986 with the publication of Keyfax, A Buyers Guide published by Virgin Books. He has since written more than a dozen books on music and music tech while also assuming duties as the CEO of KEYFAX NewMedia Inc.

Dave Bristow is a luminary of the electronic music industry. An accomplished pianist with many albums to his credit, Dave was a key member of the Yamaha DX7 team, co-authoring a book on FM with Dr. John Chowning (FM Theory And Applications) and playing a central role in the original voicing of this landmark instrument. After his work with Yamaha Dave spent three years at Pierre Boulez’s research institute IRCAM in Paris, running the MIDI and Synthesis studio. Moving to Santa Cruz in 1995 Dave worked with E-Mu Systems on the development team for several important instruments including Morpheus, and Emulator 4. In 2002 Dave once again teamed up with Yamaha Corporation of Japan to work on the company’s FM chip for mobile phones, developing ringtones and alerts. Since 2011 David has been teaching electronic music production at Shoreline Community College in Seattle, while continuing to play demanding jazz with his quartet RedShift.

Dave Bristow is a luminary of the electronic music industry. An accomplished pianist with many albums to his credit, Dave was a key member of the Yamaha DX7 team, co-authoring a book on FM with Dr. John Chowning (FM Theory And Applications) and playing a central role in the original voicing of this landmark instrument. After his work with Yamaha Dave spent three years at Pierre Boulez’s research institute IRCAM in Paris, running the MIDI and Synthesis studio. Moving to Santa Cruz in 1995 Dave worked with E-Mu Systems on the development team for several important instruments including Morpheus, and Emulator 4. In 2002 Dave once again teamed up with Yamaha Corporation of Japan to work on the company’s FM chip for mobile phones, developing ringtones and alerts. Since 2011 David has been teaching electronic music production at Shoreline Community College in Seattle, while continuing to play demanding jazz with his quartet RedShift.

Meredith Allen is an educator and an international presenter. She currently works as an Instructional Technology Consultant, Education Ambassador and Account Manager for the collaborative, online DAW, Soundtrap. Prior to her work with Soundtrap, Meredith taught instrumental music, technology and virtual reality. She is currently located in Iowa, has two little music maker daughters and enjoys traveling.

Meredith Allen is an educator and an international presenter. She currently works as an Instructional Technology Consultant, Education Ambassador and Account Manager for the collaborative, online DAW, Soundtrap. Prior to her work with Soundtrap, Meredith taught instrumental music, technology and virtual reality. She is currently located in Iowa, has two little music maker daughters and enjoys traveling.

The key ingredient in any Master Class is hang time with the Master. Not hang time in terms of swapping jokes or sharing the peanuts but considered, observational hang time where you’re able to pick up on the vibe, the pacing, the approach to the day’s proceedings. Anyone can feel (or even say) ‘The chorus comes in too late’ ‘You’re early on the downbeat’ or ‘The kick drum is a bit muddy.’ But how and when to voice these thoughts? If the writer, or artist, or engineer feels the narrative is a discussion between equals and not a directive issued from on high, that could be the difference between good day or a great day in the studio. Possibly even between a good and a bad day? Possibly between a hit and a ‘yeah whatever’.

The key ingredient in any Master Class is hang time with the Master. Not hang time in terms of swapping jokes or sharing the peanuts but considered, observational hang time where you’re able to pick up on the vibe, the pacing, the approach to the day’s proceedings. Anyone can feel (or even say) ‘The chorus comes in too late’ ‘You’re early on the downbeat’ or ‘The kick drum is a bit muddy.’ But how and when to voice these thoughts? If the writer, or artist, or engineer feels the narrative is a discussion between equals and not a directive issued from on high, that could be the difference between good day or a great day in the studio. Possibly even between a good and a bad day? Possibly between a hit and a ‘yeah whatever’.